In the early 1920s, the leadership of the Soviet state placed abroad most of the gold reserves of the Russian Empire. The main operations in this direction were carried out by Maxim Litvinov, Deputy Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR. The funds withdrawn from Russia settled in the secret accounts of the party.

However, Litvinov's channel was not the only one through which the “worker-peasant” power squandered the national patrimony. At least a quarter of the gold reserve went with the help of railroad engineer Yuri Lomonosov, Lenin's special envoy abroad.

A key role in this major swindle was played by a man about whom it makes sense to tell more details. Nobleman Yuri Lomonosov was born in 1876 in Gzhatsk (now Gagarin), Smolensk province, received a good technical education and in 1902 became a professor at the Kiev Polytechnic University.

He had left-wing views. It is not known when exactly he joined the Bolshevik Party, but during the Civil War he was considered to have been a longtime member. During the 1905-1907 revolution, Lomonosov was a member of the Bolshevik Party. Lomonosov was a member of the Military-Technical Organization of the RSDLP, headed by engineer Leonid Krasin. The Military-Technical Organization was engaged in supplying weapons and other materials to arm revolutionary militants and prepare terrorist acts.

Surprisingly, he got away with it in tsarist Russia, although the Police Department was well aware of Lomonosov's underground activities. Moreover, in 1912, Minister of Railways Sergei Rukhlov, known for his patronage of the Black Hundreds, appointed the Social-Democrat Lomonosov assistant to the head of all railroads in Russia! After working in this position for a year, Lomonosov moved to the Engineering Council of the Ministry of Railways.

There he met the February Revolution and played an important technical role in its victory. On February 27, 1917, armed with a revolver, he showed up at the Ministry of Railways and ordered its employees to block the movement of trainloads of troops from the front sent to Petrograd to suppress the revolution. He also gave false telegrams about the seizure of suburban stations by “revolutionary detachments”, as a result of which the train with Nicholas II was sent on March 1 to Pskov, where the next day the tsar was forced to abdicate.

In the summer of 1917, Lomonosov traveled to the United States on behalf of the Provisional Government to conclude contracts for the purchase of steam locomotives. There he met the events of the October Revolution. The Bolsheviks retained him in his former position. Moreover, Lenin assigned him additional functions. In 1920, at Lenin's insistence, Lomonosov was given the rights of the People's Commissar of the RSFSR, and he was obliged to report only personally to Ilyich himself.

Lomonosov continued to live mostly abroad. He came to Soviet Russia occasionally for new assignments. His family also lived abroad. At a time when millions of Russian peasants were starving, Lomonosov's family gave lavish receptions and balls at their home in Berlin.

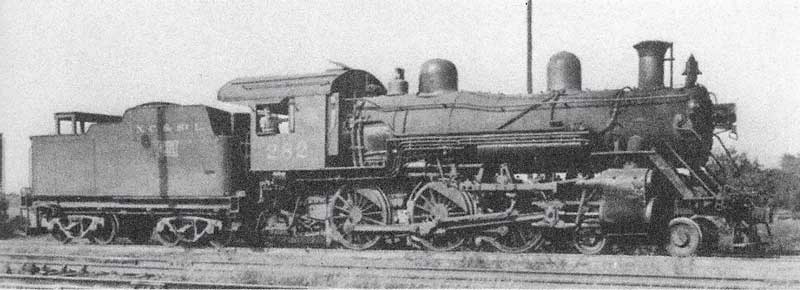

In March 1920, the Council of People's Commissars, at Lenin's insistence, approved a plan to purchase 1,000 steam locomotives abroad. The execution of the assignment was entrusted to Yuri Lomonosov, a special commissioner for railway affairs.

At that time, the Soviet Republic was experiencing an acute shortage of rolling stock. Many locomotives were idle, as there was nowhere and nothing to fix them. Nevertheless, domestic factories had sufficient capacity to make up for the shortage of locomotives.

Even more strange looked the order of 1000 steam locomotives from the Swedish firm “Nidqvist and Holm”, which produced no more than 40 steam locomotives a year. In this case, the Swedes immediately received an advance payment in gold. And, for example, American industrialists offered to supply Soviet Russia 1000 steam locomotives on credit with the beginning of payment in three years after shipment of the first batch.

The suspicious circumstances of the steam locomotive transaction were pointed out by A.N. Frolov in the new Soviet journal “The Economist” as early as 1922. Without knowing all the circumstances, he noted, however, that the republic ordered steam locomotives abroad at a triple price, when it was more profitable to produce these locomotives at home. At Lenin's personal request, the Economist was closed after two issues had been published.

The total amount of funds spent on the purchase of steam locomotives in 1920-1923 amounted to no less than 240 million gold rubles with the total value of the country's gold reserve at the beginning of 1920 960 million rubles. Even taking into account the double inflated price for each locomotive, the equipment was delivered to the RSFSR for only 41 million rubles, after which the Swedish side stopped deliveries, referring to the failure of the Soviet side to fulfill its obligations. The terms of the contract signed by Lomonosov did not provide in this case for the return of paid advances.

In the years when the Soviet Republic was suffering from the most severe famine, the amount of money spent for the purchase of virtual steam locomotives exceeded the amounts allocated for the purchase of food abroad.

The Swedish firm served only as a cover for the sale of Russian gold abroad. It was melted down, with the Swedish People's Bank stamped on the bars, and in this form it was sold to other countries. As can be judged from the indignant telegrams of Litvinov and other Soviet functionaries, the gold through Lomonosov was sold at prices significantly below market prices.

no one would allow one man to steal a quarter of the country's gold reserves. Something, and a lot, to Lomonosov stuck, but only because the case was too subtle and delicate, and no control over it for some reason could not be entrusted to Krasin, or even Dzerzhinsky. Lomonosov carried out direct directives from Lenin.”